|

ASPROM | |||||||||||||||||||

The Association for the Study and Preservation of Roman Mosaics |

||||||||||||||||||||

| About ASPROM | News & Events | Publications | Mosaics in Britain | Resources | Join ASPROM | |||||||||||||||

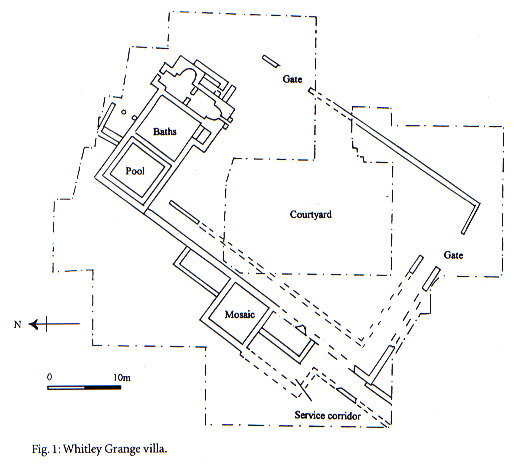

During the past three years, the Wroxeter Hinterland Project has been carrying out a training excavation at the suspected Roman villa at Whitley Grange, near Shrewsbury. The site was confirmed as a Roman villa in 1893 when a dense concentration of Roman tile and tufa suggested a bath house here, a theory confirmed by further fieldwork done in the mid-1970s. During 1995 intensive and extensive field walking and geophysics pin-pointed the site and a small area was opened at the densest concentration, which found the well-preserved remains of hypocausted rooms. Further walls were observed and in the next season the area of excavation was enlarged substantially to elucidate the full plan of the villa.

This succeeded in showing that the heated rooms encountered in 1995 were part of a much larger bath house and were not attached to a residential villa as was first suspected. Instead, another substantial wall was traced running south from the south-west corner of the bath house and attached to this were two rooms, one square and the other rectangular. The square room, Room 6, was equipped with a fine mosaic that was demonstrably contemporary with the walls of the range and thus dated it. A portico lay in front of this west wing, further evidenced by a fine column base found in the hypocaust of the bath house. In the final season of excavation, two adjoining rectangular trenches were opened which traced the main wall of the villa until it turned eastwards to form the south wing. Only one further room was located, a narrow room in the west wing symmetrical with that found in the previous season, so that the west wing consisted of just three rooms: the square room with the mosaic and two narrow flanking rooms. A wall traced from the south-west corner of the mosaic room mirrored that of the southern half of the west wing and probably represented a service corridor leading away from the buildings, although this could not be confirmed in excavation. The portico proved difficult to trace but its southern end was located showing that it had probably fronted the west and south wings. Beyond a broad gap in the south wall, which may have been an entrance, another more flimsy wall was detected which then turned northwards to close the rectangular courtyard of the villa. A second broad gate was located at the north-east corner. Only one ancillary building was discovered, a four-post structure perhaps representing a fodder or grain store that lay north-west of the bath house and west wing.

In terms of phasing it seems clear that the bath house was the earliest building and may have been built in the third century with a refurbishment in the fourth. It fell into disuse between AD 420–520 according to remanent magnetic dating and was partially robbed out. For the rest of the villa, dating must rest on the mosaic, which appears to belong to the third quarter of the fourth century on art historical grounds. There is thus the possibility that an earlier building exists on the site which has yet to be detected. Parallels for this curious villa have proved difficult to locate. The villa, except for the sumptuous bath house, thus apparently consists solely of three rooms, one with a fine mosaic, and a service corridor. The main wing and that to the south were fronted with a portico but the rest of the villa boundary was merely delimited with a simple wall enclosing a courtyard. If residential accommodation did exist, it would have to be in a separate courtyard either to the south or, less plausibly, to the west or east. Such a solution seems inherently unlikely since residents would have to cross the entire villa to reach the bath house, hardly a convenient arrangement. The theory that the rooms to the south comprise servantsí quarters and perhaps a kitchen has much to commend it. If so, then we must accept that the plan is substantially complete as we have it and that the building cannot conceivably be a farm. Rather, it should perhaps be interpreted as a dacha, somewhere to take friends for weekend fishing or hunting. The site lies ten miles from Wroxeter, roughly half a day or so in carriage or on horseback. Furthermore, the complex would have been visible from the Roman road but not accessible, since the Rea Brook runs between them so that passers-by might be impressed by the grandeur of the site and yet not be able to visit it easily. In such a setting, the room with the mosaic would have been a fitting place to spend a weekend feasting on locally caught game.

![]() Read more about the mosaic from Whitley Grange.

Read more about the mosaic from Whitley Grange.

| © R. H. White 1997. This article was originally published in Mosaic 24 (1997) 17–18. |